The work of three BCHS students has been published in the most recent edition of Albricias, a national magazine recognizing the high achievement of Spanish language students from across the country.

The students are seniors Madalyn Brand and Megan Dellenbaugh, and Jack Newell, a junior.

All entries explored the theme of human rights. Bethlehem had the most entries published of any school and is only one of two public schools in New York State to be featured.

The students submitted their work in the fall with the encouragement of BC Spanish Honor Society advisor Evelyn Ledezma.

“In the past, we have been lucky to have one student whose work is published in a particular year,” said Ledezma. “To have three of our students featured in one issue is truly a special honor.”

Ledezma said each student chose a different means to express themselves when it comes to human rights:

- Jack Newell wrote a powerful poem, El Guardabarranco, with political content made through a comparison to Nicaragua’s national bird, known as Guardabarranco, to the Nicaraguan president. Translation can be found below.

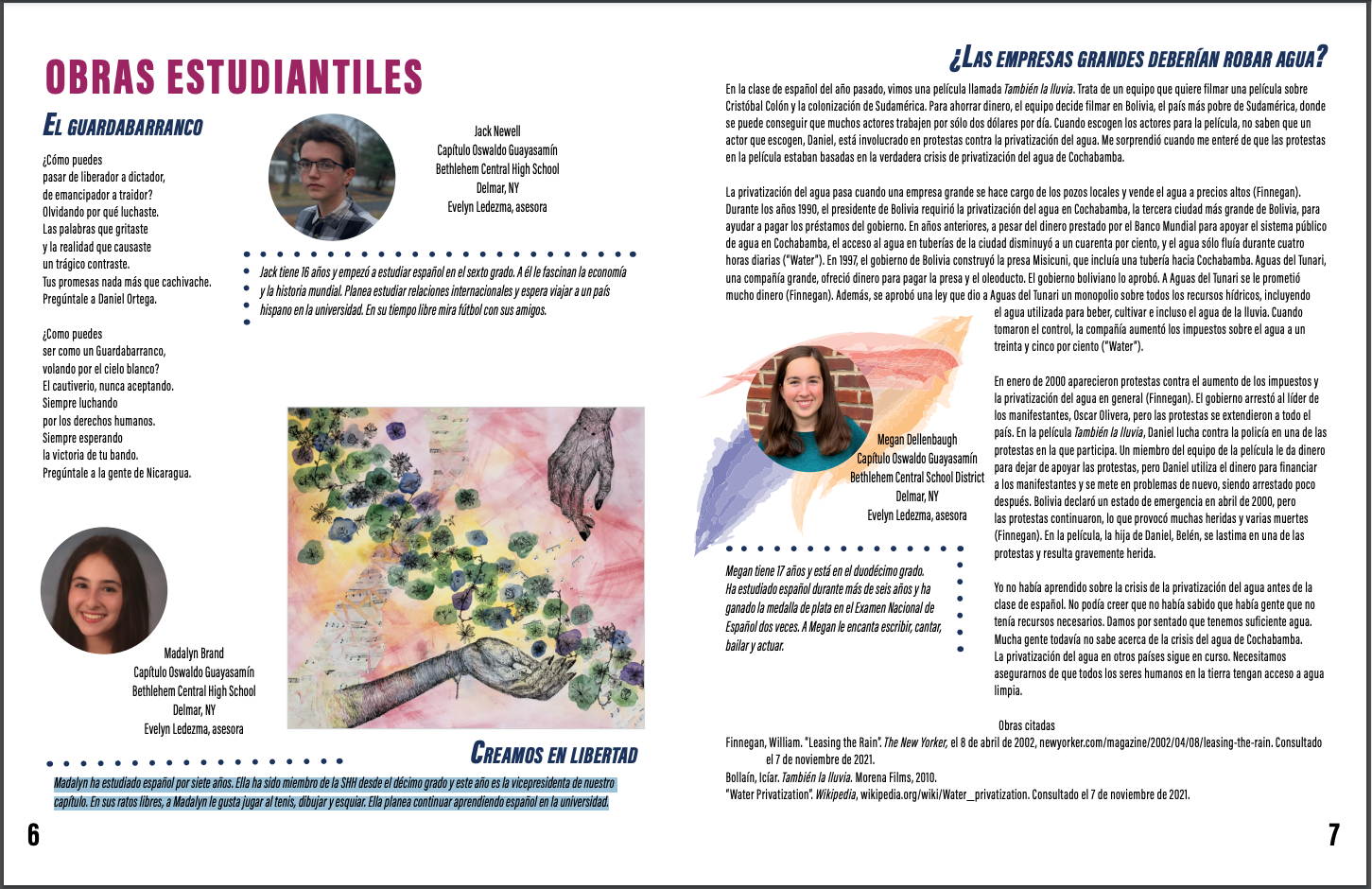

- Madalyn Brand made a beautiful illustration entitled Creamos cuando somos libres about creating in freedom. It is pictured in the magazine spread above.

- Megan Dellebaugh wrote an essay, ¿Las empresas grandes deberían robar agua?, about the water wars of Bolivia. Translation can be found below. Dellenbaugh’s essay won second prize in the prose category.

You can read Albricias online here (the Bethlehem students are featured on p. 6)

Congratulations to these students!

Translation – El Guardabarranco by Jack Newell

How can you

go from a liberator to a dictator,

an emancipator to a traitor?

Forgetting what you fought for.

The words you shouted

and the reality you caused

a tragic contrast.

Your promises nothing more than junk.

Ask Daniel Ortega.

How can you

be like a Guardabarranco (Nicaraguan bird),

flying through the white sky?

Captivity, never accepting.

Always fighting

for human rights.

Always hoping

for the victory of your side.

Ask the people of Nicaragua.

Translation – Should Large Enterprises Steal Water? by Megan Dellenbaugh

In last year’s Spanish class, we saw a film called También la Lluvia about a team that wants to film a movie about Christopher Columbus and the colonization of South America. To save money, the team decides to film in Bolivia, the poorest country in South America, where many actors can be made to work for only two dollars each day. When they choose the actors for the film, they don’t know that an actor they choose, Daniel, is involved in protests against water privatization (Laverty). I was surprised when I learned that the protests in the film were based on the real crisis of privatization of Cochabamba’s water.

Water privatization is when a large company takes over local wells and sells water at high prices (Finnegan). During the 1990s, Bolivia’s president called for water privatization in Cochabamba, Bolivia’s third largest city, to help repay government loans. In previous years, despite the money lent by the World Bank to support the public water system in Cochabamba, access to piped water in the city declined to forty percent, and water only flowed for four hours a day (Wikipedia). In 1997, Bolivia’s government built the Misicuni dam, which included a pipeline to Cochabamba. Aguas del Tunari, a large company, offered money to pay for the dam and pipeline. The Bolivian government approved it and Aguas del Tunari was promised a lot of money in return (Finnegan). In addition, a law was passed that gave Aguas del Tunari a monopoly on all water resources, including water used for drinking, farming, and even rainwater. When they took control, the company increased water taxes by thirty-five percent (Wikipedia).

In January 2000, protests against tax increases and water privatization in general appeared. The government arrested the leader of the protesters, Oscar Olivera, but the protests spread throughout the country (Finnegan). In the film También la Lluvia, Daniel fights the police in one of the protests he attends. A member of the film’s team gives him money to stop supporting the protests, but Daniel uses the money to fund the protesters and gets into trouble again, eventually being arrested (Laverty). Bolivia declared a state of emergency in April 2000, but protests continued, resulting in many injuries and several deaths (Finnegan). In the film, Daniel’s daughter, Belén, is hurt in one of the protests and suffers a serious injury (Laverty).

I had not learned about the crisis of water privatization before the Spanish class. I couldn’t believe I hadn’t known that there were people who didn’t have the necessary resources. We assume that we have enough water, but many people still do not know about the Cochabamba water crisis. Water privatization in other countries continues. We need to ensure that all humans on earth have access to clean water.